What a funny question asking a Fulani his relationship with nature! I mean how someone who is closely tied to his livestock can resist green and healthy savannas trees and shrubs embellished by a diversified grass layer, the whole landscape crossed here and there by a network of limpid streams?

What a funny question asking a Fulani his relationship with nature! I mean how someone who is closely tied to his livestock can resist green and healthy savannas trees and shrubs embellished by a diversified grass layer, the whole landscape crossed here and there by a network of limpid streams?

Culturally and socially, Fulani’s’ life cycle is define and determine by cattle. They live from cattle and for cattle raised freely throughout West African savanna lands. For generations, Fulani people survived desertification, water shortage and drastic environmental changes including temperature increase thanks to this type of breeding and living. Whether this breeding system is nowadays sustainable or not can be discussed and is still under discussion. My point of view is that it depends where and what one stands for and what are actual outlook and perspectives.

Who better know the great value of trees, shrubs and grasses than those who suffer from water scarcity, forest degradation and environmental change? Who have more stakes for ecosystem preservation, restoration or protection than those who have to walk thousands and thousands of miles searching for water, fresh grasses for cattle and forage trees to feed their animals and themselves?

So, if you understand the dependency of Fulani people on trees, water and grasses, then you probably apprehend my strong interest in joining this project and my strong motivation as a Fulani myself.

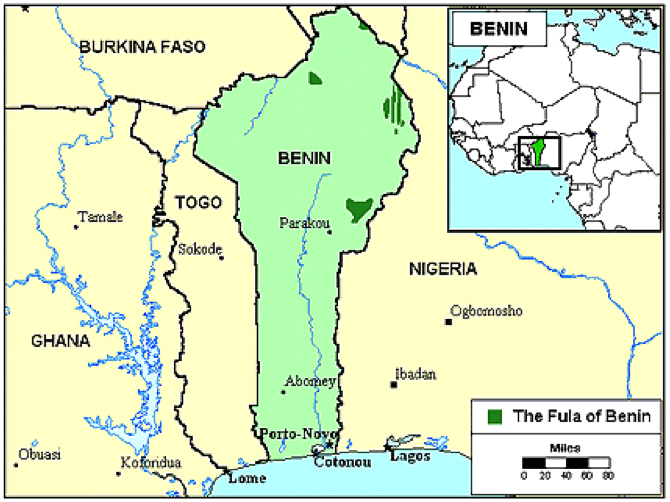

From West Africa, I am jumping straight to Benin, my home country and especially Parakou, the city where I grow, study and become what I am. The strong dependency of the residents on Okpara reservoir for rough drinking water and the anticipated temperature increase and rainfall decrease in the region is very worrisome. This justified my fight for urgent action, thanks to CIL ongoing project on climate change hopefully.

The Okpara water reservoir represents the only source of drinking water supply for more than 266 000 people and contributes to the livelihood of six riparian municipalities (APIC ONG, 2011) including Parakou, the third largest city of Benin. Yet, during the last decades, this reservoir lost over half of its initial storage capacity estimated to about 5,750,000 m³ due mainly to the growing and uncontrolled extension of farmlands on the reservoir catchment area. The ongoing sedimentation of the reservoir is likely to result in detrimental consequences for Parakou city and riparian localities where potable water demand is currently estimated to 7,233,003 m³/year doubling thus the active storage capacity of the dam (2,650,000 m³/year). Recent studies have revealed also various water quality degradation issues mainly due to the increasing use of herbicides, insecticides and fertilizers by upstream farmers.

The Okpara water reservoir represents the only source of drinking water supply for more than 266 000 people and contributes to the livelihood of six riparian municipalities (APIC ONG, 2011) including Parakou, the third largest city of Benin. Yet, during the last decades, this reservoir lost over half of its initial storage capacity estimated to about 5,750,000 m³ due mainly to the growing and uncontrolled extension of farmlands on the reservoir catchment area. The ongoing sedimentation of the reservoir is likely to result in detrimental consequences for Parakou city and riparian localities where potable water demand is currently estimated to 7,233,003 m³/year doubling thus the active storage capacity of the dam (2,650,000 m³/year). Recent studies have revealed also various water quality degradation issues mainly due to the increasing use of herbicides, insecticides and fertilizers by upstream farmers.

On-field survey in Parakou confirms above trends. Indeed, throughout the year, residents of Parakou regularly face several days to weeks of tap water shortage (with a high increase in dry seasons) together with heavy physical and moral constraints for families and especially women and young girls who have to spent several hours looking and harvesting water from wells when available. At the same time, household income is monthly stressed by the increase of water bills due to increasing water treatment costs and other associated expenditures.

In riparian localities of the reservoir including the villages of Kpassa (6689 inhabitants) and Kika (9,967 inhabitants), residents face two major threats namely an exposure to water borne diseases and climate risks including yearly inundations.

Indeed, though some manual pumps exist in the village, they are largely insufficient and their geographical distribution hinders their effective use. Therefore more than 30% of Kpassa inhabitants still depend on the reservoir for drinking water and various household needs especially in dry seasons.

Over the last five years, about 20 persons have died by drowning (field survey in Kpassa, 2015) due to the intense flow of water on the reservoir lateral spillway which crosses the main and unique road linking the villages of Kpassa and Kika and Benin to Nigeria. Important destruction of farms located downstream the reservoir is also recorded each year.

To foster actions in favor of natural ecosystems restoration is essential for local communities’ adaptation and mitigation of climate effects. Trust building, dialogue and consensus among local stakeholders and various scale stakeholders are key to reach sustainability goals. By participating to the design of the project and through a close participation and active involvement of local experts (NGOs, civil society and local leaders including women), I strongly expect that our project on climate change will trigger profound transformation at local scale in favor of the protection and sustainable management of Okpara reservoir. That is for instance to participate and support river streams’ rehabilitation, riparian forest restoration/reforestation and to develop a mechanism likely to lead to a win-win situation for both stakeholders.

[Cheik Abdel Kader Baba, Benin & Germany]

teresa de Frankfurt at kader: how are you and how ist your initiative coming? I have not heard from you during many weeks and would like to learn about the follow-up of your Story. Have you contacted People and motivated them to work with you, what are the Problems and gains?

Happy new year from